Fantasists Already Thrive In Our World

As the baseball season approached recently, I went looking for a preview magazine. A magazine in this digital age? Others rolled their eyes, too.

Wal-Mart reduced its magazine/book section by two-thirds and hid it over by electronics. Nothing on baseball.

Down at my local employee-owned grocery store [though I have always wondered if all those owner/employees kept their jobs after the introduction of self-checking], there was no real baseball magazine.

There was one on fantasy baseball so make-believe general managers could put together make-believe teams to compete in make-believe leagues.

Only make believe – though often played with much real money. Yet, that seems to be sufficient to satisfy more people every day. Fantasy baseball and fantasy football. Do you root against a once-favorite team if it would help you in your fantasy world?

Automatic vocal tuning can make any bad singer [preferably pretty] a star. Internet anonymity creates fantasy critics [with no accountability]. An exploding artificial intelligence boom creates fantasy authors complete with fantasy biographies.

Now comes the Apple Vision Pro, “a revolutionary spatial computer,” Apple says, “that seamlessly blends digital content with the physical world … and lets users interact with digital content in a way that feels like it is physically present in space.”

Would a user end up lost in space? Trapped in unreality? Would some be tempted to spend most of their time in a fantasy world?

More so than many do today?

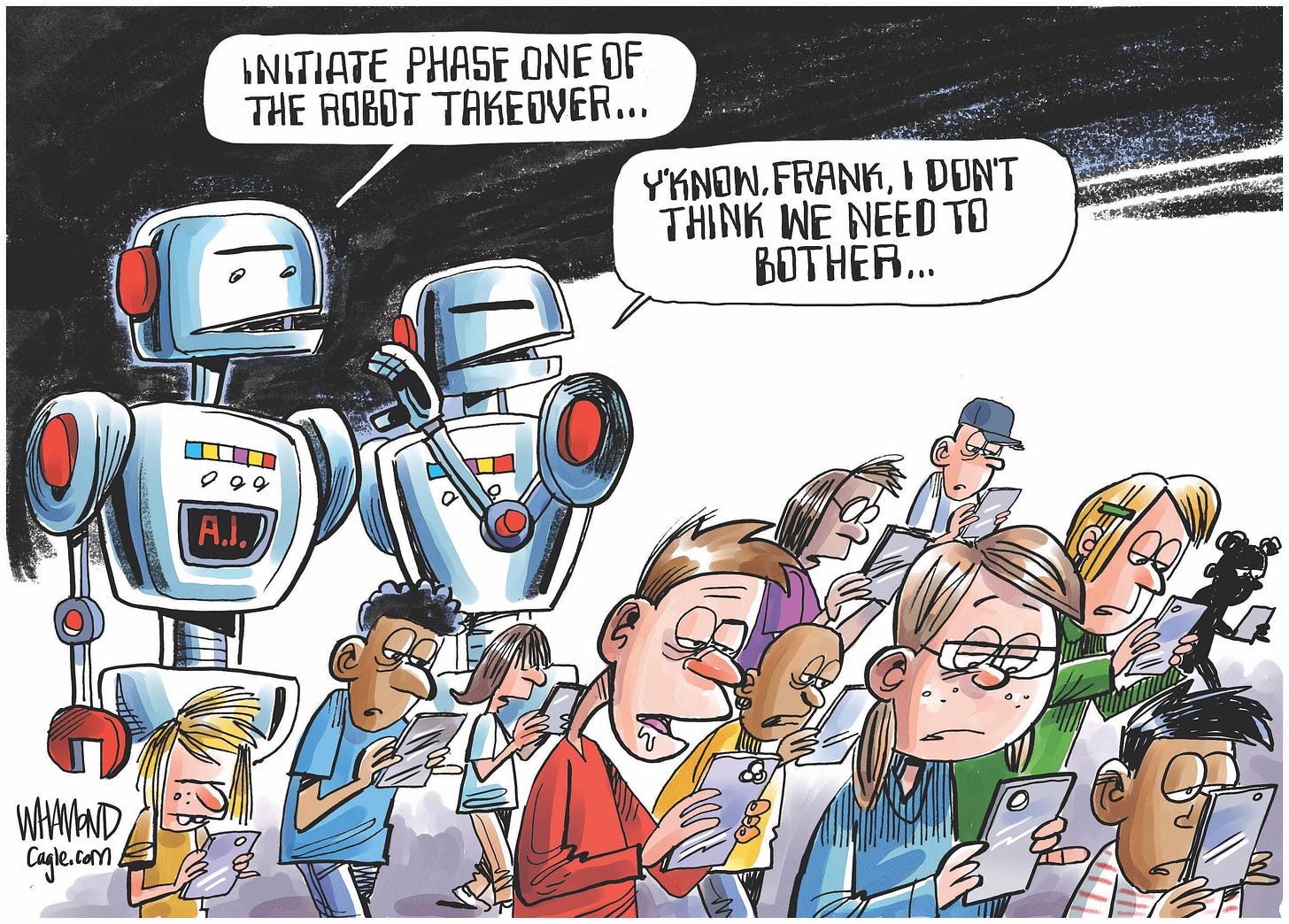

I barely dip my toes in the social media pool. I am not on Facebook, X, Instagram, TikTok or any other online platform. But their influence is touted perpetually by jealous conventional media – and political allies, who insist we have to get our message to people who live looking down at their phones.

Are these fantasy worlds? Well, the participants create public personas and craft them carefully, trying to impress other members of an ethereal community. There is even more deliberate masking than in daily interactions.

US Cellular – a prime enabler of these circumstances – has begun advocating a “Phones Down for 5” challenge, “to reset our relationships with technology and open up more time for human connection.” And it says consumers could use the mantra to put their phones down for five minutes, five hours, maybe even five days.

The company says that, “on average,” people check their phones every three minutes. There must be some other dinosaurs beside me out there to compensate for those who watch everything on those tiny screens all day and into the night.

The figure of the gamer in the basement has been around most of this century, and most TV criminal procedurals have tapped this stereotype for master criminals or naïve victims. But there’s a blurred field between stereotypes and archetypes. Those escape artists from what they see as the confines of reality have much more company than we usually acknowledge.

Technology has abetted this escapism. It was a logical step from headsets that put one inside a museum to avatars that permitted interaction with the avatars of others in pre-staged worlds with new identities.

Such scenarios have proven attractive for many people. Those folks, certainly, plus inquisitive others will be intrigued with the possibilities of participating in an Apple Vision Pro world of their own creation. The only limits are their imaginations.

Or maybe not. In March, Nature Neuroscience published a research paper from the University of Geneva that reported on two artificial intelligences talking to each other in which one AI performed “a new task based solely on verbal or written instructions.”

And then, “After learning and performing a series of basic tasks, this AI was able to provide a linguistic description of them to a 'sister' AI, which in turn performed them.”

The project was designed for robotic purposes, but such capabilities could develop to where an AI device could connect with the unreality device of our escapenaut and make the interactive decisions itself. A user could choose a deterministic life under the guidance of the system or a more flexible, free will, system where user autonomy would make one omnipotent

.

Either variation comes pretty close to Cartesian dualism, where a purely physical human body is inhabited by a non-physical mind.

That which Gilbert Ryle mockingly called “the ghost in the machine” has fallen victim to 400 years of logic and neuroscience. But a “machine ghost” operating a machine creating a virtual reality in a user’s mind seems plausible in the future.

Furthermore, keeping up with technological progress can prove as dizzying as the results.

At the first of April, Science Daily reported that University of Texas engineers had created a device that allows a user to manipulate video games “using only your brain” to direct one’s actions.

They have built a brain-computer interface where “subjects wear a cap packed with electrodes that is hooked up to a computer. The electrodes gather data by measuring electrical signals from the brain, and the decoder interprets that information and translates it into game action.”

The device was originally intended “to help improve the lives of people with motor disabilities.” Its extension into entertainment seems inevitable.

The whole point of an Apple Pro Vision or similar device would be to create one’s own world where the user presides supreme – or willingly submits to Calvinistic digital Fates.

I have read enough [too much?] Spenser to see some attraction in slaying dragons and rescuing fair damsels. It would be cool to drive a curveball deep into the gap in right center with the bases loaded.

And, in a way, we see some of that today with people “self-identifying” to suit their needs and goals. On-line dating profiles and former Republican U.S. Rep. George Santos come to mind. The American curse of extended infancy, deliberately delayed adulthood, seems to be a variant on this theme.

Interaction is the key. People would not necessarily be passive objects subjected to the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune unless they chose a deterministic option – or the power pack failed.

As part of a massive renovation of Disneyland Paris, the People of the Mouse promised an interactive Wonderland experience where customers would be able to direct the action.

Jessica Nicole of insidethemagic.net reports:

“One new show expected to debut later this year will bring even more entertainment to the park with its unique offering – the guests will be able to participate and influence events throughout the show ...

“The show will be inspired by the colorful and curious world of Alice in Wonderland. According to SortirParis, a Paris travel site, the ‘show will combine different disciplines, for a vibrant and dynamic musical performance,’ which will allow guests ‘the unique opportunity to play a decisive role in the show, actively participating in the outcome of the adventure.’”

Talk about going down a rabbit hole. Watch out, Alice!

This appears to be a community participation project. The individual manipulations promised by new technologies likely would be preferred by many.

Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt says that young people’s social media dependence has, in effect, rewired their brains. The youngsters – and some oldsters as well – are already living “partially online,” he says, which prevents them from being “fully present in the physical world.”

He points out, “humans are embodied; a phone-based life is not. Screens lead us to forget that our physical bodies matter.”

In 2001, Cameron Crowe’s movie Vanilla Sky portrayed Tom Cruise’s character’s life within a lucid dream – an unreality where he directs the action. He loses control at the end, but romances Cameron Diaz and Penelope Cruz along the way. Women-phobic incels might relish such a scenario.

Digital omnipotence could prove addictive. As with everything else regarding amusers and abusers, dangers exist as well. While some might find a cyber-catharsis creating and reveling in their deep fake worlds, others would likely feel compelled to try to extend their fantasy powers among non-participants.

Omnipotent and omniscient in a brave new world, we could be laying the groundwork for a fifth volume of Joseph Campbell’s Masks of God. He started with Primitive Mythology, then moved to Oriental Mythology and Occidental Mythology before arriving in the late Middle Ages at Creative Mythology. His main example of the latter was the creation of the myth of romantic love by the troubadours, which flourished in the following centuries until it has an established place in today’s Western culture.

The new volume could be called Personal Mythology, and its digital origins would come in handy since it would take cyberspace to include everybody’s personal mythmaking. The problem of participants disconnecting long enough to log their results could be solved by another function that recorded them as they happened. [Wait for it.]

The title of Campbell’s first volume reflects a scholarly bias against pre-literate cultures. That they have no written record does not lessen the awe of believers when confronting the marvel of existence.

And oral histories contain evidence, such as the shift from an agriculture to hunting culture experienced by the Lakota/Nakota/Dakota [Sioux] tribes when they emerged from what is now Minnesota onto the Northern Plains. Pte San Win [White Buffalo Maiden] brought them a new paradigm to ensure the continuity of the group.

Making a similar exodus toward their new promised land a few years earlier, the Cheyennes received their new revelation from Sweet Medicine, who came down from a mountain – Noavosse [Bear Butte] – with a new message.

The volumes on Eastern and Western myths have more written evidence and, thus, more detailed accounts of how the religions of Eurasia arose and experienced continued creative evolutions through the centuries.

Those who grow up within such systems do not realize their arbitrary origins. In Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Robert M. Pirsig addresses a similar situation regarding mind/matter dualism:

“They are just ghosts, immortal gods of the modern mythos which appear to us to be real because we are in that mythos. But in reality they are just as much artistic creations as the anthropomorphic Gods they replaced.”

Not all proposed changes meet universal approval [most start as heresies], which often results in conflict and sects. Furthermore, some of the most radical rewritings have arisen in the name of fundamentalist reform: a call to return to an old-time religion – as creatively envisioned in modern times.

Unfortunately, one constant through doctrinal changes has been a violent intolerance among those who disagree with each other as to what is orthodox and what is heresy. Education is anathema to mythmakers, and fundamentalists in particular, since the lessons of history reveal that the eternal flux also extends to people’s thoughts, theories and religions.

Lately, several religious writers have cited this evolutionary process while explaining how many evangelical Christians have embraced Donald Trump – who exhibits none of the virtues that defined Jesus’ message and, in fact, brags about his lust, greed and hatred. [Who did Jesus hate?]

Writing in The National Catholic Reporter, Daniel P. Horan observed, “what Trump has been offering them in return is not a vision of authentic Christianity, but a different religion called by the same name.” He elaborates: “This pseudo-Christianity bears a superficial resemblance to the real deal, but lacks the moral exhortations, scriptural foundations or doctrinal grounding.”

Yes, all myths are “creative” – as will be any new ones. They are created at one time and place and then massaged through the ages, taking new emphases to fit the changing times. The creative myth of romance is seen as such because it emerged within a literate, record-keeping age.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints is not yet 200 years old. The antipathy and violence which greeted early members – including the murder of founder Joseph Smith – can be seen as the reaction of 19th century Americans to the claims of a new revelation. Smith’s assertions did not fit the accepted mythos.

It is easy to extrapolate that reaction back to ancient, educated, cultured Romans when told of yet another son of yet another god being born with a Dionysian message cloaked in intolerant dogma. They were not impressed.

The Mormons have proven their adaptability over time, first by banning polygamy in order to gain statehood for Utah. Some dissenters moved to Mexico; others still practice polygamy in Utah and Arizona with little governmental interference.

Polygamy, of course, is acknowledged in the Old Testament. It was also common among Native Americans. When a government agent told Comanche Chief Quanah Parker that, since he was settling down, he would have to pick one of his wives to stay with him and send the rest away, Quanah replied, “You tell them.”

The LDS later abandoned the white supremacy of early doctrine to avoid boycotts, become more welcoming to new Third World converts and to protect the competitiveness of Brigham Young University’s athletic teams.

They are certainly not the only group to display doctrinal flexibility.

William Miller preached that the world would end on Oct. 22, 1844. Millerites flocked to his teaching from many denominations.

Unless we are living in someone’s dream in an alternate universe, Miller’s prediction did not come to fruition. Many Millerites returned to their original churches. Two groups assessed the situation and crafted the Seventh Day Adventists and Jehovah’s Witnesses.

American protestants marshaled different evidence and created northern and southern versions of themselves at the outset of the Civil War. Currently, many of those denominations are redefining themselves in relation to LGBTQ+ members.

Then, too, there is a very apocalyptic message in words attributed to Jesus. This required a gloss when he did not return during the lifetime of anyone hearing that message.

Very creative justifications. The notion of original sin does not exist in Judaism, and, thus, was not part of Jesus’ teaching. Original sin was the brainchild of Bishop Augustine of Hippo in the fourth century. [I have always thought that he, like Jung, was seeking justification to minimize his own bad behavior.]

But these examples represent Western tendencies, where ironclad doctrines mask much background malleability.

In India, where Hindus recognize multiple deities, Santoshi Maa arrived in the 1960s. She was welcomed into the pantheon as useful for those in need of a goddess of joy, happiness and satisfaction.

She emerged at about the same time that the Rolling Stones were complaining about their lack of satisfaction. Something in the air back there? Probably something always in the air just looking for a new expression in a world whose mythologies become too confining.

Satisfaction means different conditions for different people. For Epicurus, it meant a mellow, sustainable imperturbability. For Mick Jagger it meant, “tryin' to make some girl, who tells me ‘Baby, better come back maybe next week.’”

Epicurus was no epicurean in the modern pejorative sense. [“If it feels good, do it!”]

As Simon Blackburn explains in The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy, Epicureanism meant “to live well” but “not to live in the hedonistic trough the word Epicureanism now suggests after centuries of propaganda against the system.” Rather, for Epicurus’ followers, the goal is a long, pleasant life full of variable enjoyments, and not “merely … volatile sensory pleasures.”

But, as Blackburn reports, the anti-Epicurus propaganda goes way back. In the first century of the common era, we find Seneca saying that Epicureanism “has a bad name, is of ill repute, and yet undeservedly.”

An adherent of Democritean atomism, Epicurus sought his happiness within the real, physical world. He acknowledged gods, but his were indifferent and took no part in human affairs. His was a steady gaze that would probably eschew virtual [un]reality, viewing it as another mythical crutch.

He opposed such delusions in his own time. He would likely do so today – when most people on the planet live in virtual worlds populated by gods and demons and angels and ghosts. [I have seen two such waking dreams.]

They live in make-believe worlds, and have organized themselves in such numbers as to force others to participate in their fantasies.

They choose to sleepwalk through life, dwelling in different fantasy worlds. Reason cannot penetrate their proud denial of truths or their prejudicial views. “Fanatics have their dreams,” as Keats says.

They embrace their fancies as if comforting friends that might protect them from change, from reassessing their lives and rearranging their ways.

Non-believers are subject to execution in 14 Muslim countries. In fact, Iranian rapper Toomaj Salehi was recently sentenced to death for songs supporting the protestors who took to the streets in 2022 when Mahsa Amini died after being taken into custody by Iran’s morality police, which had detained her for not wearing a hijab.

Politicized Hindu nationalists in India have stepped up discrimination against their Muslim neighbors. The mess in the Middle East rests largely on the claim by Israelis that they have a “God-given” right to the territory of others.

American Manifest Destiny had a less divine, but equally effective, sanction.

Our Christian nationalists [who misrepresent both Christianity and patriotism] push for nationwide conformity to their peculiar interpretations of what they consider holy scriptures. Other interpretations do not count.

Reality frightens those who cherish their illusions. In their hearts, they realize they proclaim allegiance to ideas not reflected by their actions and resent the evidence exposing their hypocrisies. They abhor self-awareness. They view “wokeness” as a curse; they would rather be dreaming within their fantasy worlds.

They prefer make-believe old fables to the stern reality of the limiting Logos. They forfeit understanding in favor of fictive lives inside daydream delusions. [The Monkees could sing a song about that.]

Pseudo-reality devices would only be another variant of this human tendency to avoid an uncomfortable world that pays little heed to our desires. Those who need such escapes would welcome them.

Adults, not so much.