It is an outlook born of my newspaper upbringing.

Back when small-town newspapers had more department heads than they now have employees, there were rivalries to contend with. Everyone considered their work the most important. Everyone took pride in the product and had ideas about how to make it better.

The office staff had the least direct influence. The press room had technical proficiencies to prove its worth, but, of course, relied upon others to provide the raw material to print.

The back shops, with deadline-saving typists and X-acto knife-wielding makeup specialists, were usually staffed by the workers with the most tenure. Young reporters and photographers were expected to get their training and move on to better wages. Ad salespeople often burned out. Except for the bosses, the clerical corps changed often.

And their long investment in the paper and the town made those in the back shop most protective of the paper’s standing in the community. They could set young reporters and editors straight on how a story might be received.

One of the first rules I picked up from Sam Pendergrast, my first editor, was, “Always lie to circulation.” Getting the paper into the hands of our readers was somewhat essential. Agreed. But circulation managers considered their schedules sacrosanct. News cycles are not as regular.

Real conflicts rarely reared their heads – except between the newsroom and the advertising department. The former wanted to get as much news [the paper’s product!] as possible into print. The latter felt the pressure of ensuring the paper’s profitability.

The battle ground was the news hole. Ad directors were charged with providing the dummies [page templates] for each edition. They figured out how much classified space they needed and then placed the retail ads on the pages.

The tighter the pages [the more ads per page], the greater the profitability – less newsprint and ink, lower overhead. The tighter pages also meant less room for news.

Those of us laying out pages – at this time by hand on 8”x10” dummies – would see the ad space eliminated from our consideration by Xes. And that’s how I have always seen advertisements, even on the finished printed pages. I just don’t see advertisements.

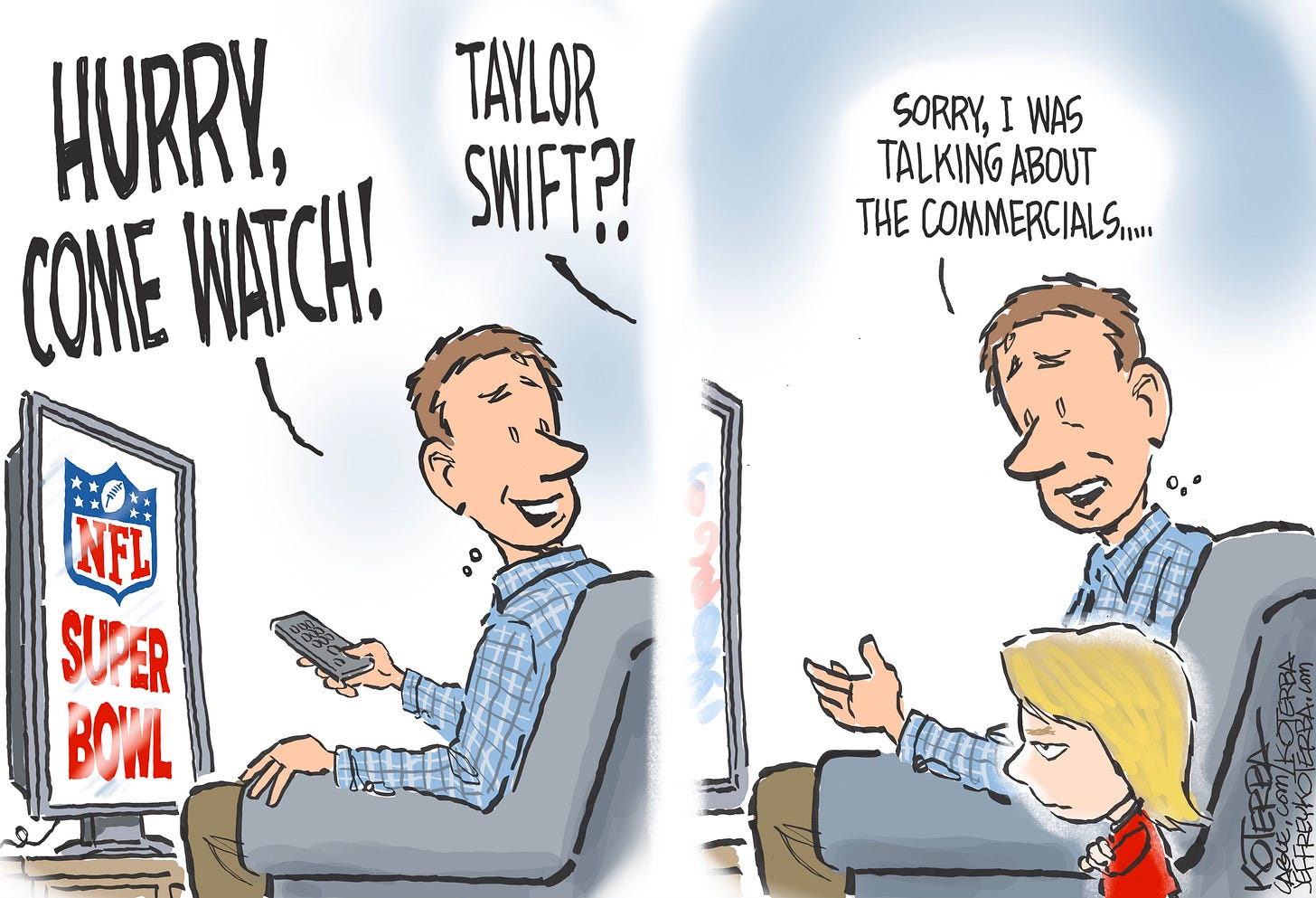

So, when I say I don’t understand the hoopla surrounding high-priced ads for the Super Bowl, you know where I’m coming from.

Madison Avenue has pulled yet another fast one on our consumerist society. Getting free publicity for should-be-paid-for advertisements. Making people whose personal indebtedness grows daily think they need to watch [and absorb] calls to buy, buy, buy more, more, more.

For two weeks leading up to The Big Game – as non-sponsors are required to call it in their ads – the network morning shows give us “sneak peaks” and teases of advertisements! Gosh, do they think we are so stupid as to think somebody has surreptitiously slipped should-be-paid-for advertisements out of a secret vault?

Some of the shills actually announce that their network has been paid for product placements. But these should-be-paid-for ad “reveals” are treated as news stories.

And, come next week, there will in-depth analyses of which ads were best, which were the most sentimental, which stars surprised with their appearances, which should-be-paid-for advertisements get another round of free exposure – eating up air time that should be devoted to news stories that might offend the conglomerates who own the companies getting the free ride.

I don’t care now. I won’t care then. I’ll be changing channels trying to avoid this travesty. It’s just the way I was raised.

The same free exposure can be extended to all the campaigns of a recent former president. And if the media doesn’t change its style of coverage, it’s possible to help elect him again, ads not withstanding.