Hughes Van Ellis’ death last week at 102 was a painful reminder Oklahoma is far from atoning for one of the ugliest chapters in its history.

Ellis was among three remaining survivors of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre in which marauding whites murdered hundreds for no other reason than the color of their skin and leveled what was then a prosperous business district hailed as Black Wall Street.

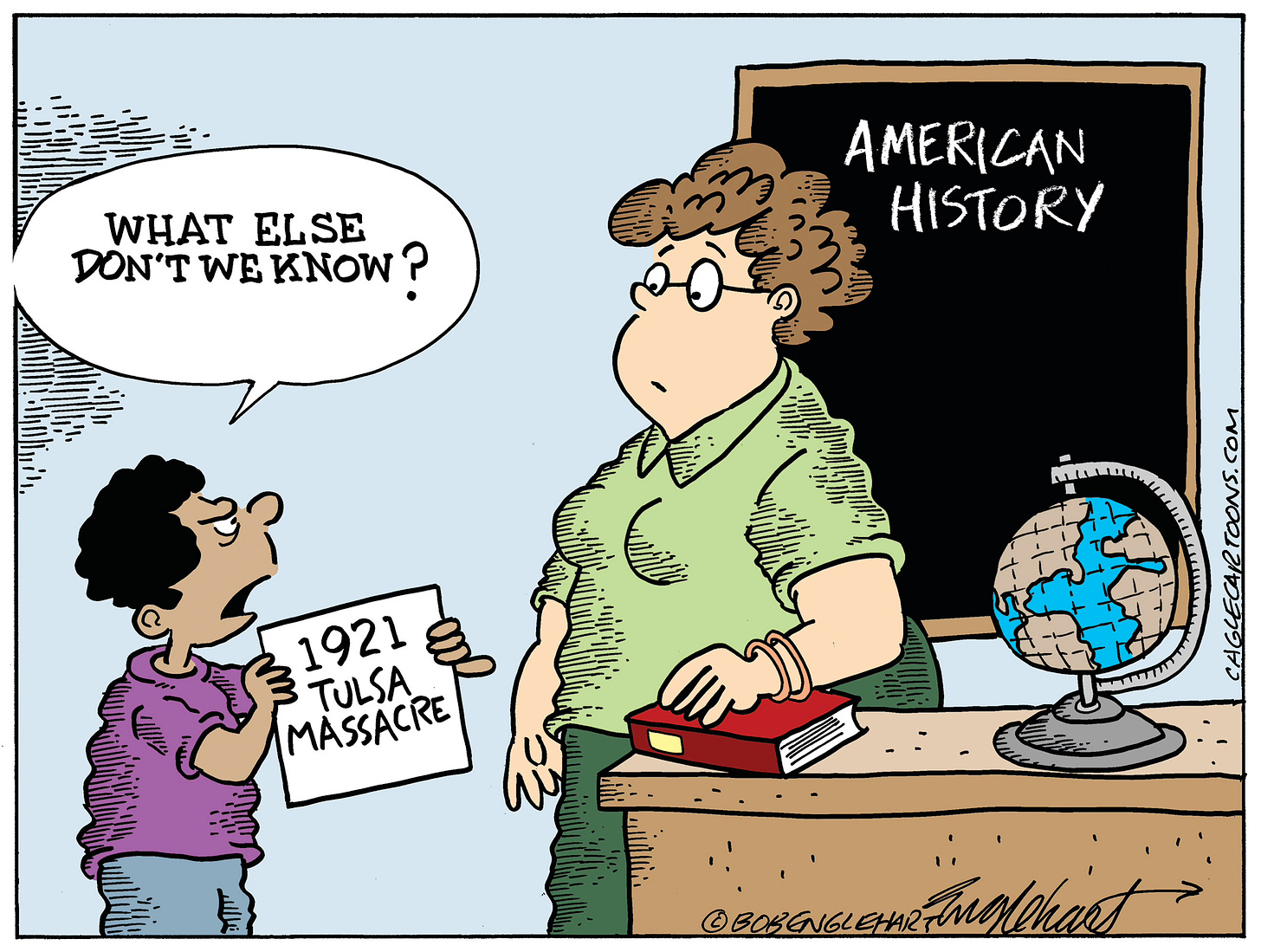

As is now widely known, the city, county and state swept the carnage under history’s rug for most of the 20th century. Bodies were buried in unmarked, mass graves. Killers and arsonists returned to their everyday lives as if nothing had happened. Survivors who chose to remain were left to try to rebuild amid virulent racism.

It took 80 years for the state to formally acknowledge the massacre in 2001’s Tulsa Race “Riot” Commission Report. It took two more decades for Tulsa to begin excavating a section of Oaklawn Cemetery that evinced a mass gravesite.

But when it comes to doing anything tangible to acknowledge that wiping out an entire community negatively impacted generations to come, the resistance among Oklahoma’s white-dominated officialdom remains as fierce as ever.

In effect, the Powers-That-Be are playing out the clock on making things right for those who survived the carnage and their progeny.

Two years ago, Ellis pleaded with members of Congress: “Please do not let me leave this earth without justice.” Now, his 109-year-old sister Viola Ford Fletcher and 108-year-old Lesslie Benningfield Randle are the only survivors left with hopes of seeing it.

In early July, state District Judge Caroline Wall dismissed a lawsuit with prejudice that sought compensation from the city and others for their complicity in the destruction of the area known formally as Greenwood. In August, thankfully, the state Supreme Court agreed to hear an appeal of the ruling by the self-styled “constitutional conservative” judge.

Why is this so hard for Oklahoma’s mostly white leadership? It doesn’t take a world-renowned economist to recognize the massacre wiped out generational wealth – losses from which many survivors and their progeny never fully recovered. Just take a drive through poverty-riddled north Tulsa.

Other locales aren’t so resistant to reconciling their past. Four years ago, for example, the Chicago suburb of Evanston committed $10 million for reparations to Black residents for discrimination and a lack of access to housing. It also is pursuing programs that address gaps in education and economic development.

In an effort to jump-start state-level atonement here, Tulsa Rep. Regina Goodwin, whose family survived the massacre, hosted a recent interim study that explored the “status and progress” of the state commission’s modest 2001 recommendations, including compensation for survivors and their descendants and scholarships.

“You have to repair the harm that was done,” she said. “The generational wealth that was lost, the homes that were burned down, the businesses that are forever gone.”

Sadly, the recommendations largely have gone unfulfilled, though last year legislators committed $1.5 million for scholarships. Even so, what in 2001 was envisioned to help 300 students annually only was able to provide 20 scholarships this year.

It’s clear some elected officials, at both the state and local levels, take a get-over-it approach to the massacre. Others worry that compensating victims could set a precedent that financially burdens future state and local governments.

Such thinking is short-sighted. With $4 billion in state savings, what better time for a modest investment in the future of Black Oklahomans whose paths to success were short-circuited by a massacre from which our state and local governments failed to protect them?

As Goodwin put it, “There’s no statute of limitations on doing the right thing.”

Thanks for this article. I didn’t know Chicago committed $10m or that we put $1.5m toward scholarships last year. It’s just a drop in the bucket compared to what should be committed, obviously, but it gives me some hope that it might have opened the door for additional financial justice in the near future. You’re right - with the current surplus, it’s time.