Twenty-two years ago, Oklahomans voted to enshrine “right-to-work” in the state Constitution. No longer could union membership be a requirement for employment.

Corporate-backed interests sold it as giving workers freedom-of-choice and as an economic development tool that would help the state attract new industry and jobs. But make no mistake: it was really about busting unions and diminishing their political clout.

So, how’s it working out for workaday Sooners?

According to World Population Review, Oklahoma still languishes nationally – No. 43 in median household income, $55,862. In fact, compared to our neighboring states, we’re ahead of only New Mexico [$53,992] and Arkansas [$52,528], but well behind Colorado [$82,254], Texas [$66,963], Kansas [$64,124] and Missouri [$61,847].

Some boon, eh? More like right-to-work … for less.

The data is worth pondering in the wake of the United Auto Workers’ near-flawless execution of strikes against the Detroit Three automakers – the latest chapter in what is emerging as a full-blow working-class rebellion.

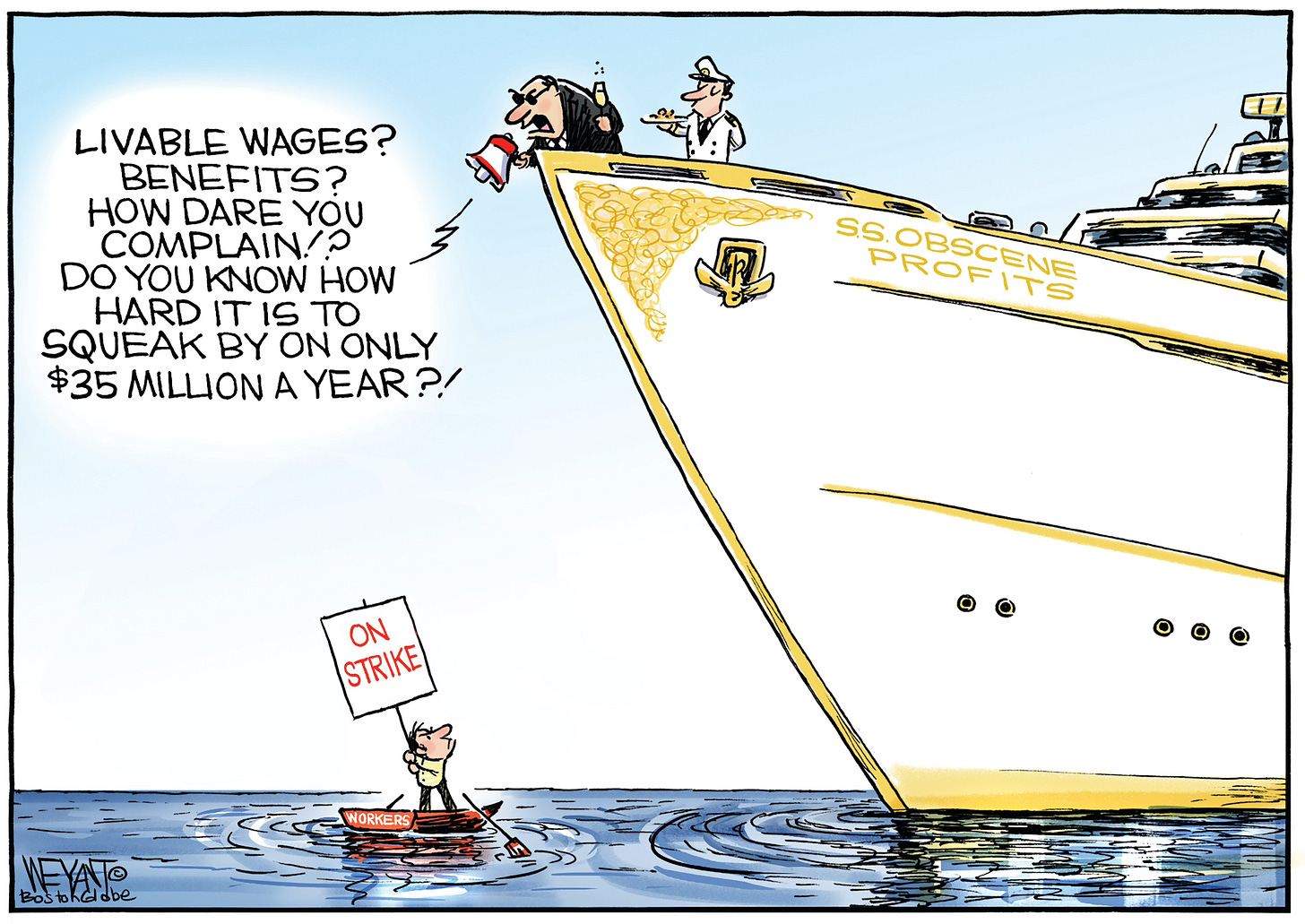

What’s fueling it? Well, for a half century, a tsunami of corporate profits flowed to the top. Last year, for example, CEOs were paid 344 times as much as the typical worker – up from 21 times as much in 1965, according to the Economic Policy Institute. This year, the long-simmering workers’ revolt exploded – 22 major strikes, 17 at corporations. Hollywood writers and actors. UPS and healthcare workers. Even university employees.

All secured significant pay hikes and more job security, demonstrating that – as The New Yorker’s John Cassidy put it – “even in the fissured and outsourced economy of the 21st century, organized labor can still wield considerable power, especially in favorable economic conditions.

“That isn’t a surprise to anybody familiar with labor history, but it is a lesson that in recent decades has often been lost, or deliberately obscured.”

Unions were dealt severe blows starting in the 1970s when activist investors mounted hostile corporate takeovers and demanded fatter profits. Companies outsourced jobs abroad, shifted operations to right-to-work states and fired workers who sought to organize or dared to strike – a blueprint made possible by Ronald Reagan’s axing 11,000 striking air traffic controllers in 1981.

Slowly, but surely Americans have come to grips with this breathtaking transfer of wealth that all but broke the middle class. In the 1950s, 75% of Americans surveyed gave organized labor a thumbs up, according to Gallup, but support plunged to just 48% in 2009 after The Great Recession. This year, Gallup found 67% approved of unions, including 72% who sympathized more with writers than TV and film production studios and 75% who sided with autoworkers.

The UAW, led by Shawn Fain, seized the moment, parlaying strong support from President Biden, sky-high industry profits, and a tight, post-Covid labor market into contracts that provide 25% wage increases and more worker protections over the 4½ years of the contract.

The Detroit Three already are warning the new contracts will require customers to pay hundreds of dollars more for each new vehicle produced. Seriously? On top of enormous profits, their CEOs were paid an average $25 million last year – five times the $5 million average at other automakers. They can’t simply share a small portion of the bounty with their employees?

Even Henry Ford knew he needed to pay his assembly liners more … so they could afford to buy the cars they produced.

The autoworkers’ successful six-week walkout won’t immediately rebalance the C Suite-assembly line disparity nor will union membership in Oklahoma – about 88,000 in 2022, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics – suddenly mushroom.

But the series of recent union victories is another sign the pendulum is swinging back – from the fat cats to those who get the real work done.

And, yes, it’s even happening here in ruby red Oklahoma, where Midwest City’s Starbucks recently became the state’s fifth to take steps toward unionization.

This is cause for celebration.